Ever wanted to punch a positivity junkie in the head?

Me neither. That would be mean. But I can see why you might be tempted.

In 2000, the American Psychologist, devoted its millennial issue to positive psychology. Fourteen years, and hundreds of books, studies, programs and websites later, ARGHHH.

Enough already.

Sometimes it’s easy to feel positive. To see the world in a shiny happy light.

Like when the video of your two-year old and the dog on a slide goes viral and now you have a book deal traveling the world writing about dogs on slides.

Feeling good is easy.

A few entries in your gratitude journal, and you’re there.

But what if cool things happen and you still feel deeply sad?

What about when you feel irritable or insecure and afraid?

What if you feel depressed or anxious and you just can’t shake it?

Cultivating attitudes of optimism, gratitude and kindness etc, sounds like solid advice. But there’s a dark side that’s rarely spoken about.

The Positivity! movement implies that bad moods and periods of darkness are not optimal, that we should do something to change them. But as any gardener knows, it’s in darkness that a seed germinates and begins to grow.

Believing we should be something other than we are, is like saying we’re not good enough.

Which isn’t positive, or self affirming.

The gratitude zealot

Whenever I come across someone who talks about how positive they are, or who is on a crusade to teach other people to be more grateful, it worries me.

My first thought is always—Oh boy, they’re in trouble. What are they doing with their grumpy, I’m-not-good-enough thoughts? It’s not possible to be positive all the time.

If at some later date, I hear they’re depressed, while everyone else is shaking their head saying, but they seemed so happy, I think—of course this happened.

It’s not unreasonable given their beliefs.

The interesting (and confusing) thing is

The positive thinking crusade has been around for over 150 years. It’s typically traced back to the New Thought movement that sprang up in reaction to fire and brimstone Calvinist religion.

But in the last 30 years it’s moved out of the fringes and into the mainstream. It’s no longer seen as some hippy, free love idea, it’s based on science. The science of “positive psychology.”

Which is interesting, don’t you think?

How is it that such learned, well-meaning, sciency type people have got so off track?

I’m so pleased you asked because I’d love to walk you through how science fails us in this regard, and what I think the real secret to feeling happier is.

The history of science (in 97 words)

Science is the organization of thought, based on reproducible experiments.

It’s not a new thing.

There have always been individuals with inquiring minds, who make discoveries that propel our understanding forward.

But in the past few hundred years the degree to which we, as a society, turn to science has grown exponentially.

Evidence based analysis is the perfect tool for some things: Like for monitoring the health of our planet. Developing life saving antimalarial drugs. Or creating tools like my Wacom drawing tablet. (I love that thing)

But where we once used the experimental model only for hard sciences—maths, physics, chemistry—we now use it across all areas of society. Including wishy washy disciplines like nutrition, sociology and psychology.

Research and analysis have become accepted as the only way to know anything.

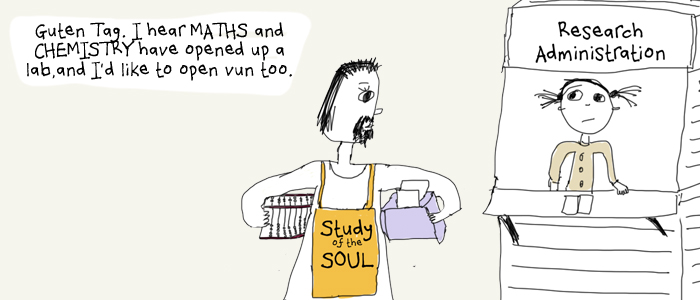

Did you know that “psychology” used to mean study of the soul?

I love this.

The term “psychology” was first used in the early 16th century by Croatian humanist, Marko Marulic, in his book, Psichiologia de Ratione Animae Humanae and literally translates as study of the soul.

Three hundred years later, everything changed when in 1879 German scientist William Wundt established the science of psychology as an experimental field.

He proposed that the mind could be measured and the nature of being human could be understood through scientific means.

For a long time the focus was on treating people who were “unwell.”

But in the 80’s, psychologists started to look at how to thrive: Positive Psychology.

The shocking truth about science

Science looks like it knows what it’s doing.

Science says things like:

Using ANOVAs we found a significant time effect (F=39.84, p<0.05). Plus an extrapolated correlation of what the bejeesus. Which is why carrots are orange.

Science is like the person you meet at a dinner party who is so freakishly articulate you become paralyzed with inadequacy. Oral skills you hitherto possessed are replaced with an urge to talk about small furry animals.

(Only a slight exaggeration of what I said the last time someone asked what I did.)

(Only a slight exaggeration of what I said the last time someone asked what I did.)

But just because someone uses highfalutin language, doesn’t mean that what they’re saying is correct.

When we discuss the latest research, we don’t talk about the details, we talk about the summary USA Today reprinted. But few journalists are trained in scientific analysis and most research goes to print unchallenged. Yet everyone acts as if what has been reported is true.

Now we have a simplified version of what was already questionable.

I used to be science’s bitch

If a scientific paper said, this is what these results mean, I believed it.

It was all, so, well, rigorous.

After 3 years at college, I was high on how robust science was.

Then along came Murray. A red–haired Canadian lecturer who taught me to see past the somber numbers and weighty words, and ask:

- Is this really what these numbers mean?

- What about this oddity here?

- Should we really be glossing over this area?

- Can we really draw this conclusion from these findings?

He reminded me about common sense.

Scientists like to think they’re dealing in hard facts. As if they’re measuring the world with God’s ruler. But what’s often forgotten is that all research rests on assumptions:

Assumptions that the data was collected accurately. Assumptions that the participants fairly represent the population. Assumptions that the analysis is correct.

Often the assumptions are wrong.

Remember thalidomide.

Remember margarine (You know that stuff is bad, right?)

Remember shoulder pads and leg warmers. (Probably not science’s fault)

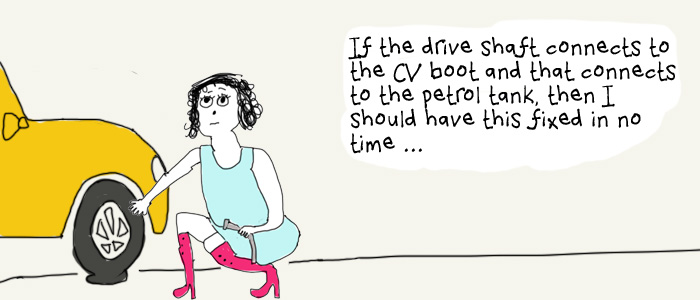

A scientist thinks like a mechanic

To a mechanic, a car is a collection of parts that fit together in a logical and predictable way. When something goes wrong, the mechanic wants to isolate what needs fixing.

A car is relatively simple. So this works well.

A scientist, like a mechanic, sees the world as a series of connected parts, and believes knowledge is found by pulling things apart.

But when you’re dealing with complex systems. This gets tricky.

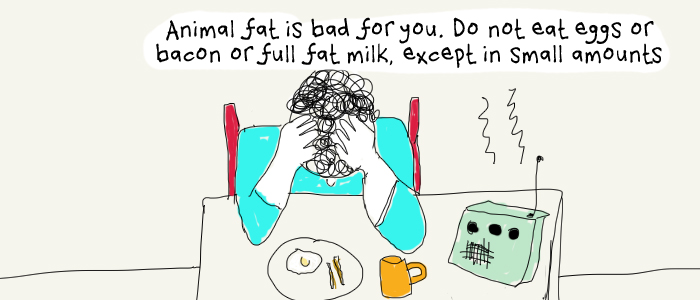

Take the study of human nutrition: Scientists look at how individual nutrients—vitamins and minerals—affect common diseases, like heart disease and cancer, as well as general health.

But food is complex and so is the human body. Nutrients don’t act uniformly across all body systems. And not everyone metabolizes things in the same way. This is why health officials, in their effort to find a one-size fits all solution, keep making mistakes.

Since the 80’s we’ve been told that cooking in animal fat was akin to cooking in Agent Orange.

And now, three decades later … full fat is back.

These flip-flops happen because scientists mistake logic for accuracy. You can be logical, but if the pieces you’re putting together (logically) are incorrect, so is your conclusion.

Yes. Some research links fat to heart disease. But other factors are ignored: Sugar. Wheat. Vegetable oils. To name a few.

And we’re all different anyway. I’m never healthier than when eating a high fat, high potato, dairy and meat soaked diet. But not everyone is.

(More on accuracy versus logic shortly)

Fuzzy wuzzy was psychology

If nutrition is vague science (nutritionists don’t think it is), happiness, is even vaguer. The mountain of assumptions is so high you could sky dive off it.

For instance, a study on happiness first needs to define happiness.

In 2004, Martin Seligman—sometimes referred to as “the father of positive psychology”— in his book Authentic Happiness, said, happiness has three parts: (1) positive emotion & pleasure (2) engagement with life, and (3) a meaningful life.

But, in 2011—less than ten years later—in his book Flourish, he changes his mind:

I used to think the topic of positive psychology was happiness, that the gold standard for measuring happiness was life satisfaction, and that the goal of positive psychology was to increase life satisfaction. I now think that the topic of positive psychology is well-being, that the gold standard for measuring well-being is flourishing, and the the goal of positive psychology is to increase flourishing.

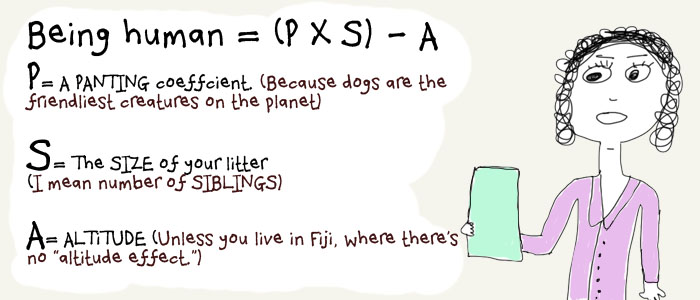

In both instances Seligman speaks as if he’s stating fact. But he’s not. It’s a stab in the dark, by a bunch of scientists trying to quantify the human condition.

Hmm.

Lets have a go, shall we.

The point is, quantifying the human condition is mission impossible.

It’s like, if you and I get together one weekend to make a net to catch a star—Sunday’s are good for me—we’d get points for trying.

But ultimately, we’re not going to succeed.

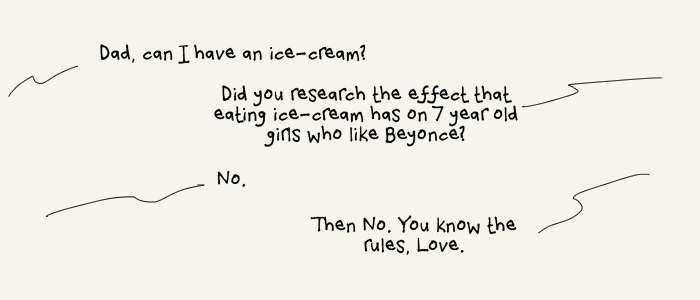

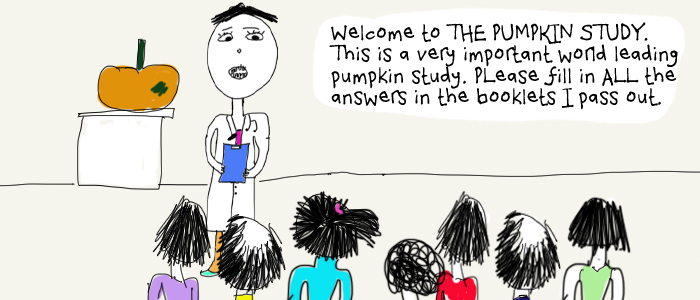

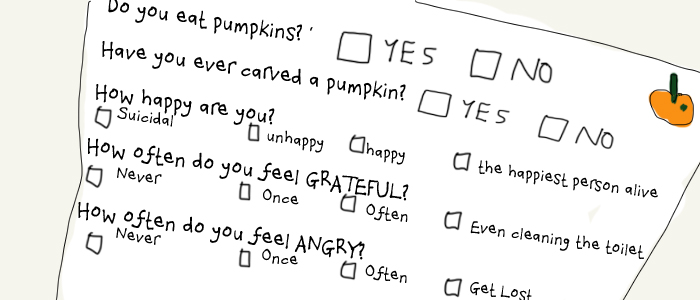

A typical psychology study goes like this

Researchers often don’t tell people what they’re actually studying.

And hide the real questions in the middle of fake ones.

The researchers then “code” the answers, converting them into numbers so they can analyze them. They’re looking for correlations and patterns.

Remember, they see themselves as people mechanics, looking for something to fix.

At last. They find something!

They have the answer!

The Pumpkin Study (actually a study on well being and happiness) draws an amazing conclusion …

They repeat the study. They talk to researchers from around the world. They’re now more sure than ever.

(They’re also relieved. The next round of funding is coming up.)

And before you know it there are 300 books and websites called “Total complete absolute utter positive positivity.”

But. But. But.

There is a gargantuan leap between noticing that people who are more happy have happier thoughts, and thinking that if we told sad people to change their thoughts, they’d feel happier.

It’s a classic case of looking for a silver bullet and finding duck pooh spray-painted silver. In science terms there is a correlational relationship, but not a causal one.

Correlation versus cause

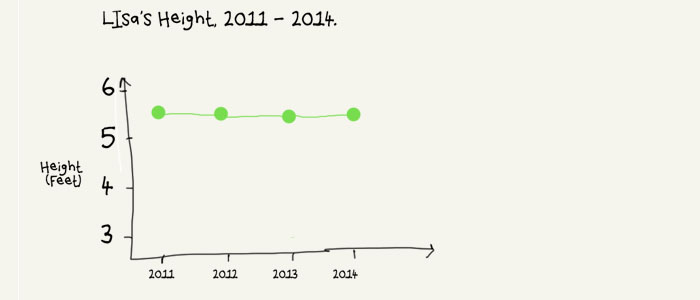

Take my height these past few years.

Steady. No growth. Nothing happening here.

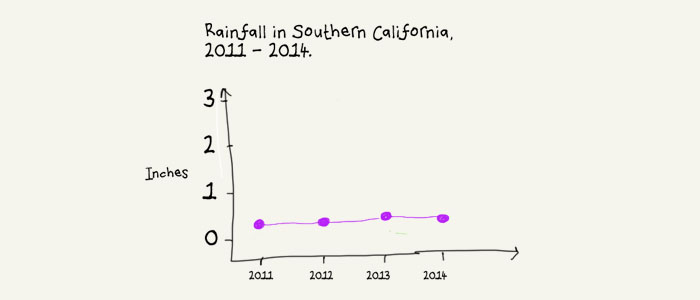

Now take the rainfall in southern California, over the same period.

This is interesting.

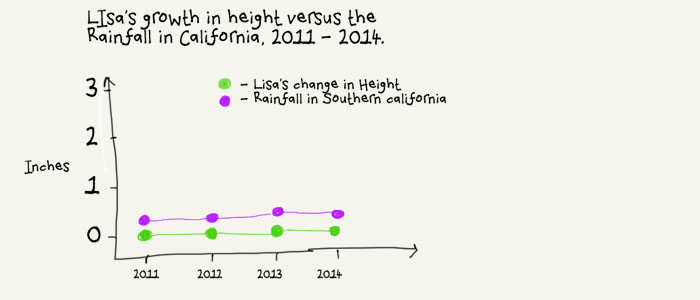

See how the shapes of the graphs are the same.

Look what happens when we look at both results together

The “R” equals 0.96! This is a very high “R” (R is the correlation coefficient. 1.0 is perfect) My lack of growth shows an almost perfect correlation with the rainfall.

And, it makes sense. I arrived in 2011, and at exactly the same time the rains stopped coming.

In scientific terms, looking for correlations is often the first step in testing any hypothesis. But it’s hardly conclusive.

Yet correlations are often reported as if the relationship is strong and causal.

Psychology isn’t wearing any clothes, don’t tell psychology

It’s widely accepted that positive thinking is good for us, yet the evidence is sketchy.

Even Seligman thinks it’s strange:

The science is quite new and the evidence, if not scanty, is far from irresistible. Why had I worn my knees begging granting agencies—often in vain—for so many years about [other topics], when now, generous individuals, unasked, would just write large checks upon hearing me lecture once about positive psychology.”

There is a general feeling among policy makers and education specialists, many of whom have jumped on the positivity bandwagon, that the science will catch up.

It’s just a matter of time.

But rates of depression have risen dramatically in the past 50 years, and people today are more stressed than ever. According to a recent Stress In America Study, teens and millenials are among the most stressed in society.

Things are getting worse, not better.

The final, and most important question is—

Are we on the right track and is the scientific model the right tool for improving well-being?

Scientists live in their heads. They’re trained to be that way.

There’s nothing wrong with this. Bloggers who draw cartoons and write about spirituality also live in their heads a lot of the time.

(Yes you)

But feeling peaceful and contented is about learning to use our mind less.

Why?

Because it’s our mind that feels insecure. It’s our mind that pushes us when we need to rest. It’s our mind that’s mean and critical. It’s our mind that doesn’t want to forgive and let go.

It’s out mind that comes up with wrong conclusions born out of fear and ego.

So why do we expect thought-obsessed scientists to have the answer? Aren’t they the last people we should be listening to?

Well-being—the final frontier

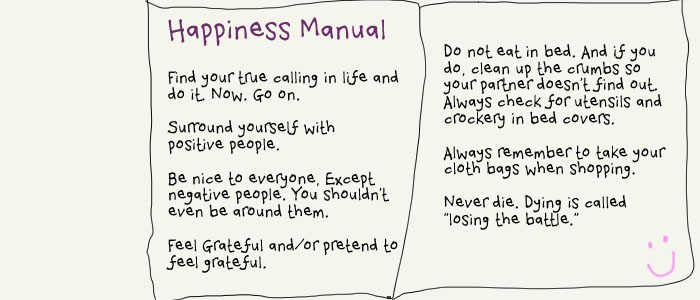

The scientific model is looking for a stock set of actions people can take for a guaranteed outcome.

A manual.

The fundamental flaw in using science to describe highly complex systems, is that in focusing on the detail, we miss the larger picture.

For genuine feelings of peace and ease, we need to go long. Not short.

We need to take a broader view:

A view that says our path is different from anyone else.

A view that says we are not our mind, or what we do, we’re the bit beneath that.

A view that says there’s nowhere to go, we’re already there. And that our job, in this life time, is to see this.

The next time you see research that says you should be something other than you are

Don’t automatically believe what you read.

Tap into what you feel guided to do. What feels right for you.

Yes, exercise is healthy, but if all you feel like doing right now is eating a bar of chocolate—or having one of your favorite vegan smoothies—and watching reruns of Friends, go for it.

And if any piece of “wisdom” makes you feel worse, question it.

In my experience, genuine insight is kind and gentle. Eye opening. And almost always comes down to uncovering another layer of how awesome we are.

To find out what to do with our cantankerous thoughts, read part II of the positivity story:

5 Tips for Inner Peace That Go Against the Positivity Movement.

Thanks for stopping by! I really am, as always, thrilled to have you here.

PS: Say “hi” below

I always love to hear what you have to say. What do you think about all this pressure to be positive and grateful? Do you even see it as pressure? Maybe it works for you? Maybe it doesn’t? I know that others enjoy hearing more thoughts than just mine. So please do leave a comment below=)

cold laser therapy device for home use

The Positivity Hoax: How the Science of Happiness Got it Wrong (Pt 1)